Conservation of Momentum: A Law of Nature That Changed the World

Solomon Hyun

January 2024 — Physics

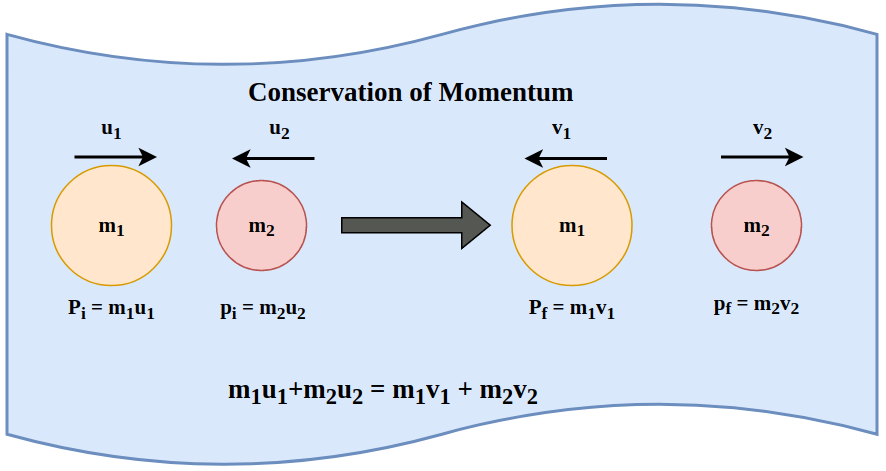

Conservation of momentum in an elastic collision. How was this concept, now used in high school physics problems, so influential?

When talking about breakthroughs in physics, conservation laws in general are not something that usually comes into our minds, especially because they literally describe things that do not change. Instead, we are captivated by groundbreaking modern developments like theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. These theories were indeed revolutionary, providing a complete shift in paradigm of how we understand the universe. However, many historians and philosophers of science will often mention conservation of momentum as one of the most impactful laws in science. Why is this the case? To discuss how the development of this seemingly boring law changed the world, we need to first talk about its history.

Aristotle was one of the earliest thinkers to write about momentum, or, more precisely, the absence of momentum. When he saw the world, nothing stayed in motion unless there was a push. For instance, a cart would come to a stop if not pushed, and an arrow, after an initial release, would gradually lose its velocity and stop. While we now know there are external forces, like friction or air resistance, that influence motion of objects, Aristotle thought that the natural state of all things was rest. Essentially, his ideas directly opposed the concept of momentum, which is the tendency of a body to remain in motion.

One of Aristotle's arguments that faced criticism was on the question of how arrows in particular can travel vast distances if they have a natural tendency to stop. He claimed that a flying arrow displaced air in its path, moving it to the back and receiving a constant push. Throughout centuries, various philosophers pointed out the absurdity of Aristotle's proposition. However, it was Ibn Sīnā, a Persian polymath during the Islamic Golden Age, who initially suggested that an arrow could travel infinitely in a vacuum, a space devoid of air resistance. Influential thinkers such as Galileo, Descartes, Huygens, and Leibniz further refined this idea into the contemporary definition of momentum, which is a quantity proportional to the mass and velocity of a moving object, and it was Isaac Newton who, through his famous three laws of motion, created a solid mathematical foundation for momentum. "How do Newton's laws relate to the conservation of momentum?" you might ask. In a nutshell, all three laws of motion are essentially restatements of the conservation law in different forms, but that's a story for another time.

Ibn Sīnā is renowned for his contributions across diverse fields, including medicine, philosophy, theology, psychology, astronomy, and mathematics.

The conservation of momentum is just one among many conservation laws. Other laws, including the conservation of energy, electric charge, and weak isospin, are equally significant for accurately describing the universe. However, what distinguishes the conservation of momentum is the impact it had on shaping people's perception of the world.

With Aristotelian physics, inferring the past of any object was impossible, as everything eventually came to a rest. This limited further scientific development. However, the development of conservation of momentum, along with the laws of motion, caused a huge shift — people realized that there are patterns. Given what the universe is doing at one point, people were now able to infer what happened before and predict what will happen in the future with extreme consistency. This is what marked the beginning of the Age of Enlightenment, which encouraged the philosophy that nature is governed by a set of strict, universally applicable mathematical rules comprehensible to humans. Fueled by this new understanding, unprecedented intellectual achievements appeared across natural science, philosophy, theology, and political theory.

The Enlightenment

The conservation of momentum also has significantly influenced how physicists approach the subject today. In contrast to other sciences such as economics, political science, psychology, biology, and, to some extent, chemistry, physics relies heavily on idealization. This involves creating models that are intentionally inaccurate but make analyses and solutions easier. Ibn Sīnā applied idealization to the flying arrow, imagining an "ideal" case without air resistance. Similarly, Newton used idealization to formulate laws of motion that are universally applicable by excluding factors like friction and air resistance, allowing physicists to introduce these factors after applying the general laws to analyze the motion of object.

There's actually a famous joke on this matter: A farmer seeks advice from a physicist to increase milk production. After a week thinking about the problem, the physicist comes up to the farmer and says "I have a brilliant solution, but it only works in the case of a spherical cow." Although making such absurd presumptions for real-life problems is impractical, the fact that we can almost over-simplify a problem, obtain its solution, and reintroduce the complexities later has taken us extremely far in physics. This is how physics has had significant progress over the last few centuries compared to any other scientific disciplines.

"First, assume a spherical cow," said the physicist.

Obviously, this doesn't imply that physics is somehow superior. Each area of science studies the world at a different level, and attempting to strip away all details doesn't work at higher levels of complexity. Thus, idealization is a technique almost exclusive to physics, and it distinguishes physics from engineering, chemistry, and biology. Therefore, the conservation of momentum not only sparked the advancement of various other fields but also played a crucial role in defining the subject of physics as we know it today.

Listen to the article as read by the author:

Bibliography

Bristow, William, "Enlightenment", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/enlightenment/

Frigg, Roman and Stephan Hartmann, "Models in Science", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/models-science/

Lee, T. (2013, September 4), "The Coase Theorem is widely cited in economics. Ronald Coase hated it." The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/09/04/the-coase-theorem-is-widely-cited-in-economics-ronald-coase-hated-it/