Attosecond Physics: Why Did It Win the Nobel Prize for 2023?

Solomon Hyun

November 2023 — Physics Source: NobelPrize.org

Source: NobelPrize.org

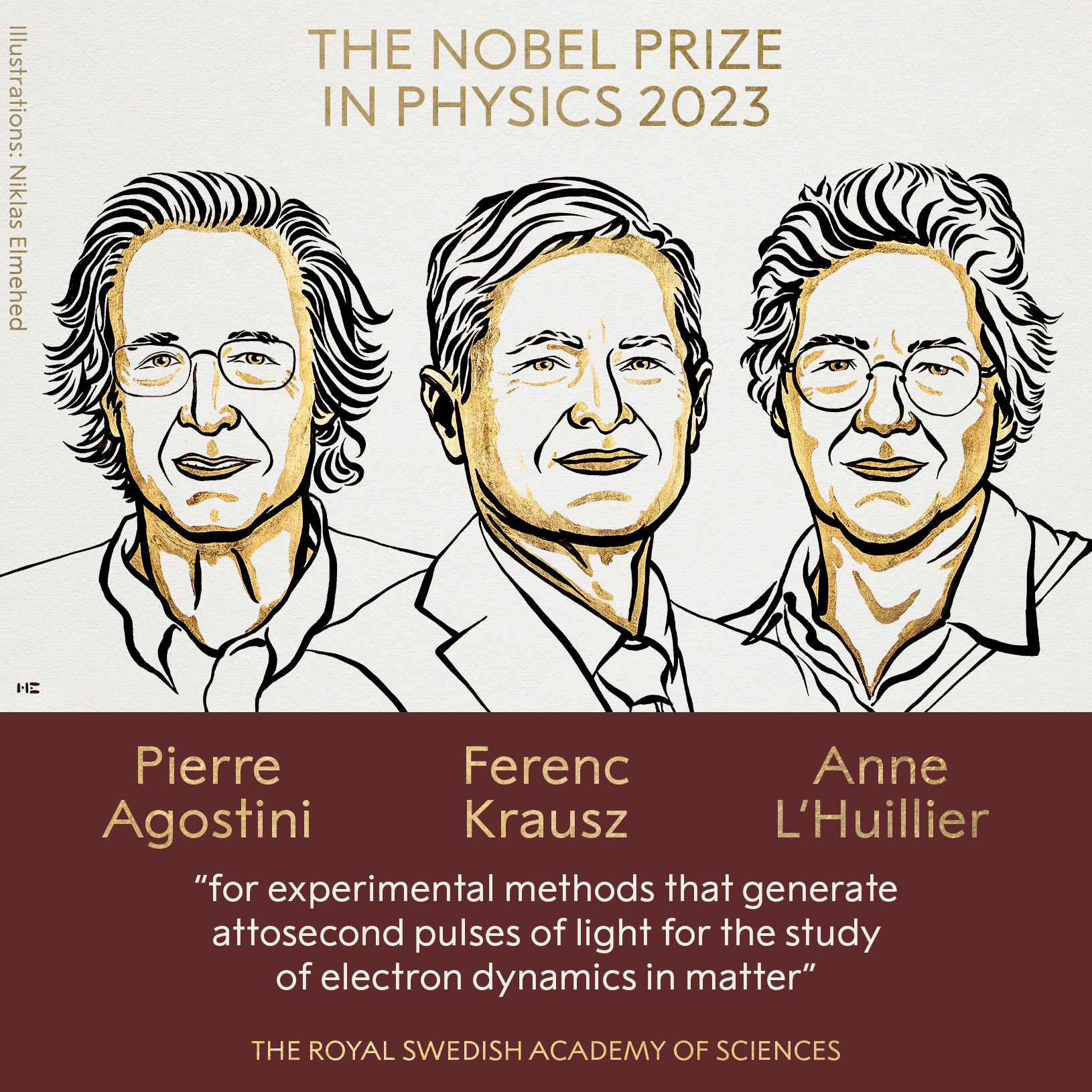

In recent years, the majority of physicists have focused on expanding our understanding of the universe by exploring either looking extremely far or extremely close. These typically capture the public's attention; for instance, the observation of distant black holes and tiny fundamental particles. However, this year's Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to three brilliant scientists for exploring a completely different dimension: time. They have pioneered technologies enabling the observation of natural processes at the scale of attoseconds, or one quintillionth of a second. To put this into perspective, there are more attoseconds in a single second than there are seconds in the entire history of the universe. While this achievement is indeed fascinating, its significance may not be apparent. In this article, I will discuss the difficulties with measuring events on such a tiny timescale and explore the potential applications of this incredible technology.

Source: Astronomy Magazine

Generally, as we observe smaller scales, processes occur at a faster rate. This intuitively makes sense because smaller objects typically have lower mass, resulting in lower inertia (less resistance to external forces). Our solar system takes about 230 million years to complete an orbit around the Milky Way, Earth takes approximately 365.25 days to orbit around the Sun, a red blood cell takes roughly 20 seconds to circulate throughout the entire body, and an electrical signal from the brain can travel to our feet in under 0.02 seconds. This trend persists even at the scale of atoms, but they are not measured in seconds or even nanoseconds. Rather, units of time like attoseconds or even smaller ones are used.

Observing phenomena at such a small scale, however, is exceptionally hard. This challenge does not come from the lack of technology but rather from the difficulty of tracking objects in very brief time frames.

Humans observe their surroundings through their eyes, which receive millions of photons (elementary particles of electromagnetic radiation) that bounce off objects. To observe faster movements that are undetectable by the naked eye or a digital camera, we need special equipment that emits photons at extremely high rates, capturing as much of the motion as possible. Imagine an invisible person moving through a room, and we use ping pong balls to gain a rough understanding of the person's motion by observing how the balls scatter. If we throw the balls slowly, the person will appear to jump between locations every few moments. On the other hand, when we release hundreds of balls per second, we will perceive a smoother motion. While lasers are commonly used for this purpose, it is physically impossible to generate a pulse of photons shorter than a few femtoseconds in length. However, this year's three Nobel Prize laureates —Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz, and Anne L'Huillier — were able to develop technologies that work around this physical barrier.

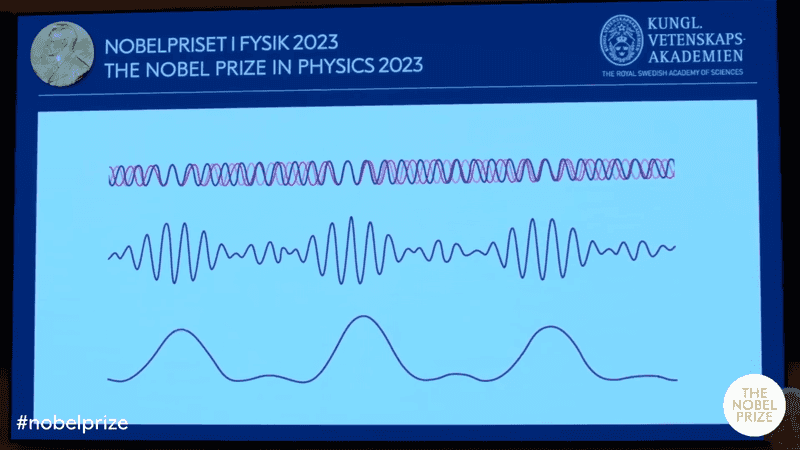

In 1987, L'Huillier and her colleagues discovered a new way to perform high-harmonic generation (HHG), a method that combines lower-energy pulses to amplify in certain areas and cancel out in others through constructive and destructive interference, respectively.

Green waves are the result of combining the red and blue waves (Source: LibreTexts Physics)

L'Huillier and other researchers soon developed a theoretical explanation for their discovery. Building on their work, Agostini and Krausz individually developed spectroscopic methods using HHG to generate attosecond-long pulses. After decades of empirical confirmation by physicists worldwide, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences finally announced on October 2nd that this year's prize will be equally distributed among the three physicists.

Creating attosecond pulses through HHG (Source: Nobel Prize Youtube)

Now, what are some applications of these methods for observing attosecond events? One significant application in fundamental research involves examining the movement of electrons. Electrons move through their orbitals in a few attoseconds, and understanding the dynamics of electrons will be immensely valuable for gaining insights into the chemical properties of various materials and biological samples.

Attosecond pulses can also be used outside observing movement. Krausz and scientists worldwide are developing techniques for molecular fingerprinting by tuning the pulses to cause specific molecules to vibrate. This has applications in medical diagnosis and pharmaceutical research and development. Additionally, faster electronics for computers is another promising application. By utilizing attosecond pulses, scientists may potentially replace photoelectrons with a third plate inside a transistor to control charges, resulting in ultrafast processing speeds.

This year's announcement is particularly significant because it acknowledges not only the breakthroughs in attosecond physics but also the achievement of Professor L'Huillier, who has now become the fifth woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics. Moreover, the research itself is very intriguing and promises a wide range of potential applications. I hope this year's prize will inspire aspiring physicists to explore topics beyond the popular fields commonly discussed in the media.